The Congressional Budget Office threw Mitch McConnell a life preserver this week, though many people may not have seen it that way. In a follow-up to its widely publicized analysis of the Senate Obamacare overhaul bill over a ten-year horizon--2017-2026--the CBO looked at the longer-term impacts of that proposed legislation. The longer term assessment was important as the Senate bill deferred most of the cuts to the Medicaid expansion until 2025 and beyond. Medicaid expansion--which extended federally funded healthcare up into the middle class--was arguably the most important element of the Affordable Care Act in reducing the size of the uninsured population.

The first paragraph of the CBO follow-up report projects a 35% reduction in Medicaid spending by 2035. While most attention in initial report was paid to the projected 22 million who would lose their insurance by 2026, that report did foreshadow what post-2026 might look like--thus the 2035 number should not have come as a complete surprise. Nonetheless, the new CBO release has, in the eyes of many, further undermined the prospects of the Senate bill. For those Republican senators who were already worried about the impact of the proposed Obamacare repeal on their constituents, the follow-up report has focused attention on the 25.5 million people projected to lose eligibility for Medicaid.

But it is the penultimate paragraph that McConnell will surely grab onto. There, the CBO frames the 35% reduction differently: by 2035, the CBO projects that the Senate legislation would reduce federal Medicaid spending from its current 2.0% of GDP to 1.4% of GDP--compared to 2.4% as projected under current law.

This is huge. For decades, the inexorable growth in entitlement spending has been the greatest fiscal challenge facing the federal government. It is the issue that sparked the creation of the bi-partisan Concord Coalition a quarter century ago, and the Simpson-Bowles Commission in 2010. Over the past half-century, each of the major federal entitlement programs have steadily grown as a share of GDP. Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security alone have grown from 30% of annual federal spending three decades ago to just under 50% today, steadily squeezing out the availability of federal funds for discretionary domestic and military purposes. Curtailing the growth in entitlement spending has long been the Holy Grail of the Republican Party, and with the CBO report in hand, Mitch McConnell can impress upon his caucus the historic importance of the vote that lies ahead.

As Republican senators grapple with this vote, it is useful to recall the importance of the 1968 presidential election in bringing them to this perilous place. That year, Republican Richard Nixon won 301 electoral votes, three shy of Donald Trump's 2016 victory. Like Trump, Nixon did not win a majority of the votes cast, though he did eek out a plurality, topping Democrat Hubert Humphrey by just over 500,000 votes, with 43.4% of the votes cast to Humphrey's 42.7%. Former Alabama Governor George Wallace--an avowed segregationist--took 13.5% of the national vote, winning five southern states of the former Confederacy outright, giving him 46 votes in the Electoral College.

Nixon, who had already lost a squeaker in the 1960 election, pounced on the opportunity that the Wallace campaign represented, and began the process--through his Southern Strategy, and law and order rhetoric--of converting southern and working class white voters from their historical home in the Democratic Party to the GOP. What ensued was a demographic swap of party loyalties that was all about race. It began with FDR's New Deal and Truman's desegregation of the armed forces, each of which contributed to the decisions of Black voters to migrate to the Democratic Party from their post-Civil War home in the GOP. That, in turn, presented an opportunity for the GOP, as Nixon advisor Kevin Phillips pointed out at the time: "The more Negroes who register as Democrats in the South, the sooner the Negrophobe whites will quit the Democrats and become Republicans. That's where the votes are." In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan solidified what Nixon started, and since then no Democratic presidential candidate has won a majority of the white vote.

Reagan advisor Grover Norquist became the architect of the ensuing GOP electoral strategy that would endure for decades. The Republican Party was then, as it remains today, the party of capital--representing the interests of the business community--while the Democrats were the party of labor. The Democratic Party--its southern variant in particular--was a transactional party. Voters delivered their votes, in exchange the party brought home the bacon. That meant everything from government jobs, to the Tennessee Valley Authority, to the massive water projects ridiculed by northerners; and, in the wake of the Hill-Burton Act in 1946, the construction of hospitals in rural communities across the country along with the requirement that they provide free care to anyone who required it.

To secure the loyalty of those voters, Republicans had to offer a tangible quid pro quo. Accordingly, Norquist constructed a coalition of single-issue voting groups--including anti-tax, pro-gun, anti-abortion, and faith-oriented position--and promised that he could guarantee the election of any Republican who swore fealty to all of his coalition policy positions.

Norquist's strategy has been effective for decades, but the tension between the day-to-day economic interests of those working class voters and the GOPs traditional pro-business policy agenda created an internal tension that finally erupted in the 2016 presidential campaign. Donald Trump saw through the hypocrisy of the GOP galvanizing its white working class "base" around social issues, while ignoring--if not actively undermining--their economic interests. He towed the line on Norquist's core issues--proposing the largest tax cuts in history, and taking strident pro-gun and anti-abortion positions--but he turned his back completely on other traditional Republican stances. He opposed globalization and free trade, and in a much more fundamental way, walked away from rhetoric around personal responsibility and small government that had long defined the Republican worldview. And included in his stock stump speech was the promise to protect entitlement programs and provide universal access to healthcare that would be better and cheaper than Obamacare.

For seven years--to the cheers of their base voters--Republicans in Congress voted time and again to repeal Obamacare. In the eyes of most of those Republicans, the goal was to roll back a massive expansion of entitlements, and they presumed that this is what the base wanted. But while Donald Trump similarly railed against Obamacare, he saw things quite differently. His supporters may not like Obamacare, but they very much wanted affordable access to healthcare. Accordingly, Trump proposed not to end the expanded healthcare entitlement, but rather to make it bigger and better; not less healthcare, but more healthcare for less money. Now, as the Senate bill is coming up for a vote, many senators are coming to grips with the fact that Trump may understand their constituents better than they do.

The healthcare debate has forced Republicans in Congress to struggle with their identity as Republicans. While, conservatives have been clinging to the core Republican belief in rolling back government and allowing free markets to work, many of their GOP colleagues are getting cold feet. The expanded CBO projections have placed the choice facing Republicans in stark relief. It has given Mitch McConnell the most powerful argument he could hope for as he seeks to sell his caucus on supporting the healthcare bill: an historic opportunity to curtail the long-term cost trajectory of a major entitlement program. Standing in McConnell's way is the growing realization among many in the GOP that the voters the Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan brought into the GOP--and who now constitute the base of the party--were never on board with much of what the GOP has long stood for. Unlike their representatives in Congress, they worry about healthcare every day, and to risk losing it is a big, big deal. The GOP will soon find out whether, for many of those voters, the problem is not that Obamacare went too far, but rather that it didn't go far enough.

Read it at the HuffPost.

Follow David Paul on Twitter @dpaul.

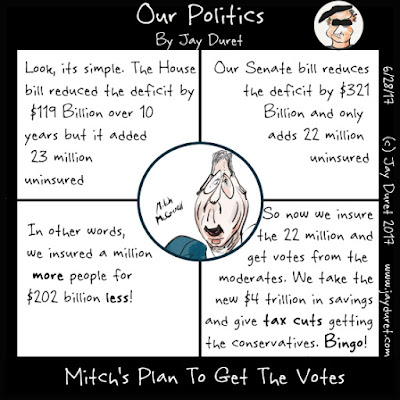

Artwork by Jay Duret. Check out his political cartooning at www.jayduret.com. Follow him on Twitter @jayduret or Instagram at @joefaces.

The first paragraph of the CBO follow-up report projects a 35% reduction in Medicaid spending by 2035. While most attention in initial report was paid to the projected 22 million who would lose their insurance by 2026, that report did foreshadow what post-2026 might look like--thus the 2035 number should not have come as a complete surprise. Nonetheless, the new CBO release has, in the eyes of many, further undermined the prospects of the Senate bill. For those Republican senators who were already worried about the impact of the proposed Obamacare repeal on their constituents, the follow-up report has focused attention on the 25.5 million people projected to lose eligibility for Medicaid.

But it is the penultimate paragraph that McConnell will surely grab onto. There, the CBO frames the 35% reduction differently: by 2035, the CBO projects that the Senate legislation would reduce federal Medicaid spending from its current 2.0% of GDP to 1.4% of GDP--compared to 2.4% as projected under current law.

This is huge. For decades, the inexorable growth in entitlement spending has been the greatest fiscal challenge facing the federal government. It is the issue that sparked the creation of the bi-partisan Concord Coalition a quarter century ago, and the Simpson-Bowles Commission in 2010. Over the past half-century, each of the major federal entitlement programs have steadily grown as a share of GDP. Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security alone have grown from 30% of annual federal spending three decades ago to just under 50% today, steadily squeezing out the availability of federal funds for discretionary domestic and military purposes. Curtailing the growth in entitlement spending has long been the Holy Grail of the Republican Party, and with the CBO report in hand, Mitch McConnell can impress upon his caucus the historic importance of the vote that lies ahead.

As Republican senators grapple with this vote, it is useful to recall the importance of the 1968 presidential election in bringing them to this perilous place. That year, Republican Richard Nixon won 301 electoral votes, three shy of Donald Trump's 2016 victory. Like Trump, Nixon did not win a majority of the votes cast, though he did eek out a plurality, topping Democrat Hubert Humphrey by just over 500,000 votes, with 43.4% of the votes cast to Humphrey's 42.7%. Former Alabama Governor George Wallace--an avowed segregationist--took 13.5% of the national vote, winning five southern states of the former Confederacy outright, giving him 46 votes in the Electoral College.

Nixon, who had already lost a squeaker in the 1960 election, pounced on the opportunity that the Wallace campaign represented, and began the process--through his Southern Strategy, and law and order rhetoric--of converting southern and working class white voters from their historical home in the Democratic Party to the GOP. What ensued was a demographic swap of party loyalties that was all about race. It began with FDR's New Deal and Truman's desegregation of the armed forces, each of which contributed to the decisions of Black voters to migrate to the Democratic Party from their post-Civil War home in the GOP. That, in turn, presented an opportunity for the GOP, as Nixon advisor Kevin Phillips pointed out at the time: "The more Negroes who register as Democrats in the South, the sooner the Negrophobe whites will quit the Democrats and become Republicans. That's where the votes are." In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan solidified what Nixon started, and since then no Democratic presidential candidate has won a majority of the white vote.

Reagan advisor Grover Norquist became the architect of the ensuing GOP electoral strategy that would endure for decades. The Republican Party was then, as it remains today, the party of capital--representing the interests of the business community--while the Democrats were the party of labor. The Democratic Party--its southern variant in particular--was a transactional party. Voters delivered their votes, in exchange the party brought home the bacon. That meant everything from government jobs, to the Tennessee Valley Authority, to the massive water projects ridiculed by northerners; and, in the wake of the Hill-Burton Act in 1946, the construction of hospitals in rural communities across the country along with the requirement that they provide free care to anyone who required it.

To secure the loyalty of those voters, Republicans had to offer a tangible quid pro quo. Accordingly, Norquist constructed a coalition of single-issue voting groups--including anti-tax, pro-gun, anti-abortion, and faith-oriented position--and promised that he could guarantee the election of any Republican who swore fealty to all of his coalition policy positions.

Norquist's strategy has been effective for decades, but the tension between the day-to-day economic interests of those working class voters and the GOPs traditional pro-business policy agenda created an internal tension that finally erupted in the 2016 presidential campaign. Donald Trump saw through the hypocrisy of the GOP galvanizing its white working class "base" around social issues, while ignoring--if not actively undermining--their economic interests. He towed the line on Norquist's core issues--proposing the largest tax cuts in history, and taking strident pro-gun and anti-abortion positions--but he turned his back completely on other traditional Republican stances. He opposed globalization and free trade, and in a much more fundamental way, walked away from rhetoric around personal responsibility and small government that had long defined the Republican worldview. And included in his stock stump speech was the promise to protect entitlement programs and provide universal access to healthcare that would be better and cheaper than Obamacare.

For seven years--to the cheers of their base voters--Republicans in Congress voted time and again to repeal Obamacare. In the eyes of most of those Republicans, the goal was to roll back a massive expansion of entitlements, and they presumed that this is what the base wanted. But while Donald Trump similarly railed against Obamacare, he saw things quite differently. His supporters may not like Obamacare, but they very much wanted affordable access to healthcare. Accordingly, Trump proposed not to end the expanded healthcare entitlement, but rather to make it bigger and better; not less healthcare, but more healthcare for less money. Now, as the Senate bill is coming up for a vote, many senators are coming to grips with the fact that Trump may understand their constituents better than they do.

The healthcare debate has forced Republicans in Congress to struggle with their identity as Republicans. While, conservatives have been clinging to the core Republican belief in rolling back government and allowing free markets to work, many of their GOP colleagues are getting cold feet. The expanded CBO projections have placed the choice facing Republicans in stark relief. It has given Mitch McConnell the most powerful argument he could hope for as he seeks to sell his caucus on supporting the healthcare bill: an historic opportunity to curtail the long-term cost trajectory of a major entitlement program. Standing in McConnell's way is the growing realization among many in the GOP that the voters the Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan brought into the GOP--and who now constitute the base of the party--were never on board with much of what the GOP has long stood for. Unlike their representatives in Congress, they worry about healthcare every day, and to risk losing it is a big, big deal. The GOP will soon find out whether, for many of those voters, the problem is not that Obamacare went too far, but rather that it didn't go far enough.

Read it at the HuffPost.

Follow David Paul on Twitter @dpaul.

Artwork by Jay Duret. Check out his political cartooning at www.jayduret.com. Follow him on Twitter @jayduret or Instagram at @joefaces.

No comments:

Post a Comment